10. DATABASE LAYOUTS

1. PRINCIPAL LAYOUTS

The Bayala databases description to this point has been based on the OVERVIEW layout, although the LINKS layout was introduced in 2. The Big Picture and pictured in Figs. 2.3 and 2.4. In addition to the OVERVIEW layout, each database has several other layouts, of which the principal ones are:

—DUMP

LINKS LAYOUT

The LINKS layout has a similar format in all the language databases. Its purpose is to reveal links a word might have in other areas of the country and hence in other languages. While the User might not often visit this layout it is surprising in its power.

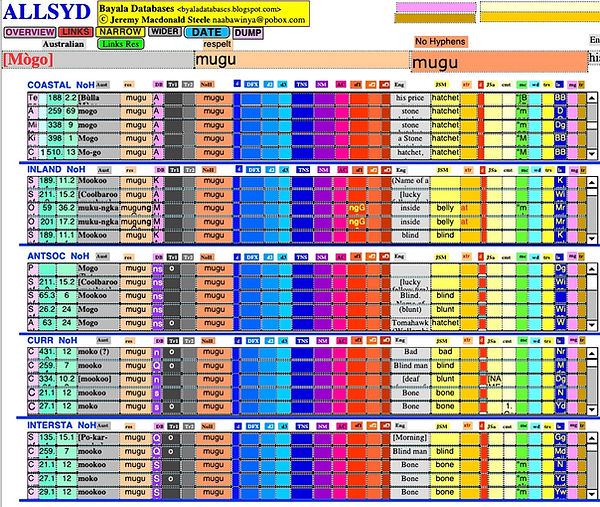

Fig. 10.1 The LINKS layout in the various databases. In this instance, at the very top, mugu meaning ‘knee’ is being looked at. But below the key entry at the top is a country-wide look at the two words mugu and ‘knee’.

Nationwide word displayer, and word finder

This screen is giving the User two astonishing sets of information. The first is this. In Fig. 10.1 on the left-hand side, all the entries in the brown NoH field are for mugu. The screen is showing all instances of this word around the country (insofar as they have been recorded in the databases). Also on the left-hand side, in the yellow EngJSM field are shown all the meanings that mugu can have in those languages.

The second set of an astonishing amount of information is on the right-hand side. Here, in Fig. 10.1 in the yellow EngJSM field is the word ‘knee’, since that, in the single record being looked at shown at the top, is what mugu means in this one particular instance. Also on the right-hand side, the brown NoH field is displaying words meaning 'knee' all around the country (insofar as they have been recorded in the databases).

If the scroll bars to the right of any panel on the left- or right-hand side are grey, this indicates there are more entries than have been displayed in that panel. The additional entries can be seen by sliding the scroll box (at the top of each scroll bar) down.

An example based on the word mugu

In the INTERSTATE database there are 44 entries for mugu. That database covers principally Queensland and South Australia, so those 44 entries are for those areas. There are many more instances of mugu in the other areas of the country.

To select another of the 44 INTERSTATE entries for mugu, on a Macintosh computer hit the right-hand arrow under the three coloured dots at the very top left of the screen, that is the arrow under the green dot. This will produce another meaning of mugu, say meaning ‘bone’. And instantly, as shown in Fig. 10.2 below, on the right-hand side a completely new array of data appears in the supporting portals below. This is because now a new word (‘bone’ instead of ‘knee’) is the focus. On the left-hand side mugu remains the same, so the information there is unchanged.

Fig. 10.2 Probably because of a change in the language being looked at, mugu's different meaning ‘bone’ becomes the focus on the right-hand side

Now in the yellow EngJSM field on the right-hand side, ‘bone’ is necessarily repeated in every instance; at the same time all the words meaning ‘bone’ around the country are given in the brown NoH field on the right-hand side.

mugu in Sydney

Australian languages generally use words of only two or three syllables. These can be, and often are, extended by the addition of suffixes, but any basic word is usually short and simple: such as mugu. This is a common word in the Sydney region meaning ‘hatchet’.

Fig. 10.3 An extract of the ALLSYD LINKS layout for mugu meaning ‘hatchet’. There are 23 records for mugu ‘hatchet' in the ALLSYD database. These are included in the 'Coastal’ portal at the top.

Is mugu, the User might wonder, used in other languages, either meaning the same thing or something else?

A search in the LINKS layout in any other of the language databases will show the answer, so long as mugu occurs in the language database being searched. (In fact mugu does not occur along the Murray River, nor in Victoria, nor in Western Australia excluding the south-west; in Tasmania it is part of longer words beginning mugu-.)

As is shown in the yellow EngJSM field in Fig. 10.3, mugu can have many meanings in different languages, these languages being indicated in the navy blue ‘langshort’ column third from the right. Clicking on any one of them will reveal its abbreviation, from which the language can be identified by the table in Fig. 7.14.

Searching in the LINKS layout

In order to search in the LINKS layout the User initiates a command, as Command-F (or ⌘-F on a Macintosh, F being for ‘find’) by inserting the cursor in either the respelt or NoH field, then types, say, mugu, and hits Enter. Likewise to find, say, ‘hatchet’ he or she places the cursor in the EngJSM field, types hatchet and hits Enter.

Only a glimpse

Everything is compressed in the LINKS display, to enable as much information to be given as possible. For this reason the columns are narrow. In addition, because the rows in the portals are reduced to five only, there are generally far more responses than can be seen in Figs. 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3.

However, what is not visible in these figures can be viewed in the database itself by using the grey scroll bars. These are the vertical bars with the white box in the middle, in each of the illustrations above, at the very right edges.

LINKS RESPELT layout

In some of the databases, particularly those covering larger areas of the country and hence more languages (e.g. COASTAL, INLAND, CURR, INTERSTATE), there is also a LINKS RESPELT layout. This is similar to the LINKS layout, the difference being that it specifically operates on the ‘respelt’ field. This field comprises the whole of the respelt form of an original record (as opposed to the stem only in the case of the LINKS layout, which is based on the ‘no hyphens’ record). For example, for the word for corroberee (translated in EngJSM as ‘dance’):

"Car-rib-ber-re" gari-ba-ri "Another mode of dancing" dance Anon (c) [c:8:11] [BB] [NSW]

the LINKS layout, based on the ‘No Hyphens’ field, looks at gari, whereas the LINKS RESPELT layout looks at the whole word garibari.

NARROW LAYOUT

There is little remarkable about the NARROW layout. It simply features narrower columns and greatly reduced numbers of display items at the top, enabling many more records to be viewed on a normal screen than on the OVERVIEW layout. Layouts such as the NARROW layout can be easily configured to have narrower or broader columns, or to have less information in the area above the fields and records, enabling more records to be viewed.

WIDER LAYOUT

Little, too, is remarkable about the WIDER layout. This time the columns are broader allowing longer records to be shown. Again the number of display elements at the top of the layout is reduced, enabling more records to be shown than is possible on the crowded OVERVIEW layout.

DUMP LAYOUT

The DUMP Layout (as described in 6. Search Portals) is essentially a slimmed down version of the OVERVIEW layout. It omits the elaboration bars and other information elements found on the OVERVIEW layout.

Fig. 10.4 [Fig. 6.9] On the DUMP layout there are three search portals on the left and three occurrences portals on the right

The DUMP layout can be useful as an alternative to using the crowded, but informative, OVERVIEW layout. It is called ‘Dump’ because most of the elements in it were dumped there from the OVERVIEW layout. It does have one new feature not found on the OVERVIEW layout: the 'Occurrences ReS' portal.

2. FURTHER LAYOUTS

THE POWER TO SEARCH

The ability to search and sort is a major feature of databases.

This ability goes far beyond finding all examples of anything, or arranging things alphabetically. For example, in an instant it is possible to find, say, not only all the records where the third letter in the ‘Australian’ field is ‘n’ (call this ‘3n’; search formula @@n*) but also at the same time where the second letter in the 'No Hyphens' (NoH) field is 'g' (call this ‘2g’; search formula @g*). On performing such a search in the ALLSYD database with around 12 000 records, 116 records meet the criteria.

It would soon be noticed, however, that some responses in the NoH field were multiple words in which the 2g was in the second or later word. And in the Australian field some responses had the incidence of 3n after a hyphen [-], or after an apostrophe [´]. When responses such as these were eliminated, only 20 records, seen in Fig. 10.5 below, meet the criteria.

Fig. 10.5 Records in the ALLSYD database with ’n' as 3rd letter in grey Australian field and ‘g’ as 2nd letter in brown No Hyphens field: 20

While a search for the 3rd letter in one field and the 2nd in another might seem silly, it demonstrates the power of databases.

By using this search power it has been possible to investigate features of the records made by First Fleet 2nd lieutenant William Dawes in 1790-91. It is useful, and easy, to make special layouts for such a purpose, such as:

—DATE

DATE LAYOUT

The purpose of the DATE layout was to help identify when a record was made by William Dawes. This was sometimes necessary to know because his notebooks were not arranged with the last page of the notebooks being the last written. Instead the pages were arranged by themes, and entries were added here and there on different pages at different times over a couple of years. All the while Dawes was learning the language, and was refining the way he wrote it down. During the course of this he altered his spelling system more than once. Knowing when he made a record sometimes helped in making a judgment on how the word should be respelt. Occasionally he noted the actual date on which he wrote an entry. This enabled it to be assumed that all the entries above that on that page had been made either on the same day or earlier.

Fig. 10.6 From the ALLSYD database: DATE layout where dates of entry are speculated upon

A search (command-F) was undertaken by placing an asterisk (which signifies ‘find any text’) in the middle blue date field (column 4: 'date of entry after'). Fig. 10.6 shows a few of the entries that resulted. In the first blue date field (column 2: 'date of entry') Dawes had himself entered the date when he made the record. Evidence in Dawes’ notebooks suggested that the entries were made after the dates appearing in the ‘date of entry after’ field. The next blue date field, with gold print (column 5: 'date of entry before') contained dates that, again from evidence in Dawes’ notebooks, indicated that the entry seemed likely to have been made earlier than the date in that field. This sometimes enabled a date of entry (column 6: 'date of entry JS tentative') to be guessed at, and entered.

Why was knowing these dates important? Because Dawes was learning the language, he knew more later than he did earlier. Knowing the dates illuminated the degree of trust one might place in a particular entry Dawes made, for, as with any learner of a language, he made occasional mistakes.

DIACRITICS LAYOUT

In the DIACRITICS layout, in Fig. 10.7 below, a search was made in the bright red column headed ‘i dot’ by using the asterisk * ‘find any text’ symbol. This brought up all instances in which Dawes used a lowercase ‘i’ including an ‘overdot’ (in contradistinction to an ‘i’ without an ‘overdot’ [ı]), the former signifying the sound as in ‘I, ivy, ire’ and the latter as in ‘in, it, ill’. This was one of several indicators used by Dawes to explain pronunciation.

Fig. 10.7 From the ALLSYD database: DIACRITICS layout showing selection of results for search for the character ‘i dot’

In Fig. 10.7, on the right-hand side, below the turquoise bar ‘Incidence of Dawes’ special characters’ at the top, there are several narrow columns tabulating Dawes’ various marks to indicate how to pronounce words. These marks, or diacritics, included overlines and dots as well as a special character ŋ. The numbers in small boxes at the bottom of the illustration are totals of usages of any particular diacritics. In this case the search was for ‘i dot’, and it can be seen on close inspection that there were 105 examples of ‘i dot’ in the Dawes material. The numbers in the left-hand bright-red column show the number of occurrences of ‘i dot’ in any particular line, or record, so in record b:21:8 at the bottom there are three such occurrences, in the words ‘Paramatin’ and 'ngirigal’.

For a computer it is no trouble to find the totals of all the other columns instead of the above search restricted to the incidence of 'i dot' examples:

Fig. 10.8 On an unrestricted search of the Dawes material the 'i dot' total is still 105, but the totals of all incidences of all the other diacritics are revealed

Dawes made use of three ‘phonological systems’, each more accurate than the one preceding it, in transcribing the words he heard used by the local inhabitants. The final column on the right in Fig. 10.9 below (‘Phono sys’ ) indicates which of these systems was in use for any particular record.

Fig. 10.9 Summary of the use of diacritics by Dawes

The total boxes at the foot of Fig. 10.9 show numbers of usages in the Dawes notebooks as a whole:

macron (or overline): 227

i no dot (ı as in ‘bit’): 336

i dot (i as in ‘bite’) 105

u overdot (u as in ‘but’): 115

ŋ (ng as in ‘sing’): 229

single dots BB (confident) 50

single dots English (confident) 12

double dots (:) BB (doubtful) 24

double dots (:) English (doubtful) 29

Not mentioned is one of Dawes’ most common diacritics, the ‘acute’ sign, above or next to a letter: á, i´. This Dawes used to indicate where the stress in a word occurred: on, or just before, the acute mark.

OTHER LAYOUTS

In all the Bayala series of databases there are several other special purpose layouts. These are easily made and have no particular significance in this description of how the databases operate.